Seisei Tatebe-Goddu: Free Diving Into Bucket Lists, Rest, and the Ocean

Having lived in 9 countries, coach Seisei Tatebe-Goddu grew up looking at the world through different lenses. She loves exploring hidden dynamics beneath the surface, whether as a coach or free diving with whales at sea.

As told to Claire Zhang

I want to start off with a specific question and see where that takes us: I recall a fun fact about you is that you do whale diving or something like that. Can you tell me more?

Sure! I free dive, which means that I don't use a tank to dive. Instead, I use these really long fins, a snorkel, and a mask.

People will ask: How deep can you go? How long can you hold your breath for? They're thinking of competitive free divers, which is…fine. But I actually find that kind of free diving pretty boring, because the whole reason that I'm in the water is to find the biggest thing near me and be in the water with that. I free dive with megafauna (yes, whales).

When I was seven, I developed a love for marine biology and wanted to become a marine biologist. I obviously didn’t follow that path, but I have always had a fascination with the ocean, open water, and marine life. Several years ago, I discovered that a friend of mine runs these whale diving trips in Tonga.

I thought: “Oh, I should really do that.” It stayed on the bucket list, but it kept getting pushed off and pushed off and pushed off.

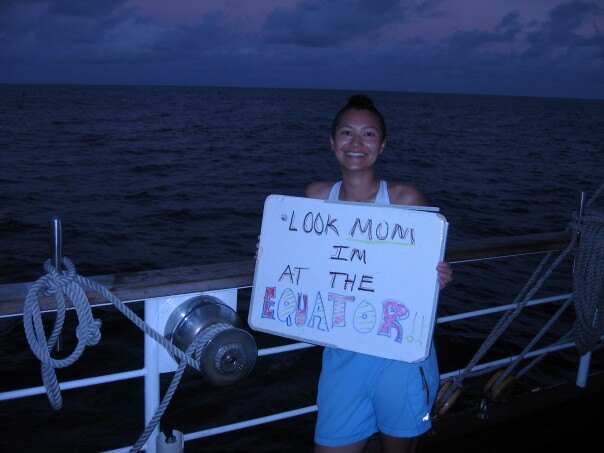

It took another five years before I said to myself: “You're either going to do this or you're never gonna do it.” So in 2018, I put in a deposit and went on my first free diving trip to French Polynesia and dove with a bunch of humpbacks. We also encountered a shark (not the nicest first encounter actually, there’s a longer story there), pilot whales, dolphins, turtles, rays. Since then, I’ve gone on several more trips.

To clarify—was that the first time you had ever free dived? Or was it the first time you went on one of those trips?

It was both the first time I went on a trip like this and the first time I’d ever free dived—which, you know, in hindsight I will do things that I think are totally reasonable and normal and then I'll tell people about them and they're like—”You did what? You didn't know how to free dive and just showed up one day?” Even free divers I know will say: “You did what?”

Had you scuba dived or anything at least before that?

I got certified when I was 13. We were living in Japan at the time and my parents used it as a bribe to get me to do other things. But then I was in Jordan for four years—essentially a landlocked country if you don’t live near Aqaba. For all intents and purposes, I was in the middle of the desert for four years and then when you're in New England or New York City…you don't want to dive in this water. I’m sure people do it, but diving in the Hudson makes you think about all the diseases you’re probably going to get. So it had been a while since I was anywhere that offered up tempting dive spots.

How would you describe the difference between free diving and scuba diving?

With scuba diving you're using a tank. Some of the competitive free divers can absolutely compete with some of the scuba divers in terms of depth. But when you’re scuba diving, you're going down deeper and staying down longer because you're breathing from a tank. It's slower and more controlled. Your movements are more controlled. In that sense it's similar to competitive free diving—if you're conserving air, you don't want to make sudden movements. You're still trying to make slow, deliberate, intentional movements.

But if you're in the water with fast-moving animals like marlin or juvenile humpbacks, you want to be able to use air efficiently while moving quickly. You’re also staying down for less time in free diving, because you're going down with a single breath. Though it’s pretty amazing how much time someone can stay down for, humans have way more lung capacity than we realize. I think the longest someone has been down with an unassisted breath (no pure O2 or nitrogen) is something like 11 minutes.

I would say in terms of the risk profile, scuba diving's pretty safe. Free diving I would say is much riskier.

And, neither of them are solo sports. Some people think: “Oh, I can go out and just snorkel around.” I'm like: “Nope. Still not a solo sport.” There are cases of people who have died because they thought ‘I can totally do this on my own.’ No, no, no. Don't do that. You should always have someone with you.

You said, about free diving: “Either I'm gonna do this or I'm never going to do it.” Can we unpack that feeling? I think that is a feeling that applies to a lot of other things in our careers and the way we make decisions. Walk me through that reasoning for yourself. Where did you find the motivation to just do it?

One of the things that I discovered about myself is that when I am sure of something, I don't ask for advice. I don't do more research, I just do it. I don't ask for permission. The gap between thinking something and doing it for me is very, very narrow.

This isn't me just patting myself on the back, but people will look at my career and they'll say “Jesus, you've done so many things and you've gotten so much done — just the breadth and variety of the things that you've touched!”

I attribute a lot of that to my ability to just have a thought and go and not really have a lot of doubt around that.

There was a period between 2013 and 2015 when I went through a series of events that were the hardest things I'd ever gone through in a compressed period of time. There was a moment where the gap between thinking something and doing it widened. We're not talking hours or days, but we're talking weeks, months.

My confidence, my ability to make decisions had been so rattled. I was just frozen. I was paralyzed. I was rethinking things. I was asking a lot of people for advice. To an extent, I was asking for permission.

One of the interesting things that I find about a lot of The Grand folks who come through is: often they know what the answer is. They're asking you a question, they're asking you for an answer, but they already know the answer.

What they really need is not for us to give them the answer, but for us to give them permission to listen to their gut and to cheerlead them to a point where they feel confident that they know what they're doing.

This moment in 2018 — I had known about these trips for five or six years.

Of course, cost is an issue as well. It's important to also have a conversation about class and the way you were brought up and taught about money—these things affect you down the road. They matter. You have to work through your beliefs around money and what you think you're worth.

In 2018 I finally had the financial means to do a trip like that, so it just came down to this question: this can either stay on your bucket list forever or you can just do it.

I think it was a combination of giving myself permission and cheerleading the decision, once I made it.

Mark Manson, who wrote The Subtle Art of Not Giving A F*ck, has an article that I use when I'm career coaching people. It used to be titled—I don't think it's titled that anymore—What flavor sh*t sandwich do you want to eat?

He talks about the fact that a lot of us will daydream about being Beyoncé, but there's only one Beyoncé. There's only one person who put in the work to become Beyoncé.

You have to love not just the outcome—the fun parts or the shiny, glamorous outcomes of the work—you have to actually believe in and want to do the day-to-day sh*tty things that are going to get you to that outcome.

What flavor sh*t sandwich do you want? Do you want it with a side of olives or a side of pickles? Do you want some ham in it? What flavor of day-to-day grind are you willing to put up with to achieve that outcome?

I love that reframing, because so often we tell people: “What do you wanna be when you grow up? What's this big thing?” And people get stuck because either they say something they'll never do, then feel badly when they don't get there; or they'll say this shiny thing and be disappointed when it's not really like that. Things stay on our bucket lists—and sometimes that's okay!

There are some things that are on my bucket list that I know I'm never going to do. But I love the fantasy. I love the daydream. It's a little bit of an escape to think about. Then there are other things that need to come off the bucket list, because those are things that you need to do.

So, I think that was a moment for me where I thought: “Get it off the bucket list.”

I love this concept of things staying or not staying on the bucket list, and actually things coming off the bucket list mean they become sh*t sandwiches actually, and not nice fantasies anymore.

Arthur C. Brooks does something called the reverse bucket list where every year he writes down all of the things that he wants to do and accomplish, and then he crosses them off. The act of crossing it off is a signal to his brain to create some non-attachment around that outcome.

We can strive for something, we can want something, but when we want it to the point of obsession or we want it to the point where we can no longer detach if it doesn't happen, or we have an identity crisis if it doesn't happen—that's really unhealthy.

So, he does this reverse bucket list process to remind himself these goals are important, but they're not the only thing. There’s something related here, around the idea: do you keep it on the bucket list or do you not? When you take it off, it becomes a little bit of a sh*t sandwich. That’s an important process for your brain.

Yes, so important. So… let’s go back to this period of time where you faced a lot of challenges and you felt that gap grow between the thought and the doing, which for you had always been short — how did you find that confidence in yourself again and close the gap?

Time. I am sure you're familiar with Tony Schwartz's energy quadrants. It's funny, because I find when I go through that with people, they tend to say:

“I'm in burnout zone or survival zone or recovery zone, but I'm really trying to move through that quickly and get back to performance.”

I look at them and I say: “I have some bad news for you... It's gonna take as long as it takes.”

You have no control over that. That's your body telling you that you need to be in a certain place for a certain amount of time.

People want to move out of recovery quickly and get to performance. The more you resist being in recovery zone when you're deeply burned out, the longer it's going to take to get back to performance zone. There are no shortcuts.

There was an element for me of just giving up. You have to imagine someone who's been super ambitious for 30 plus years and knocks down every obstacle and just keeps going — the feedback from people is always: “Gosh, you're so resilient.” All of this stuff happened to me all at once. The one point of pride I have here is that it took a lot to get me to this point. One thing after the other, nothing let up for months. Everything that possibly could have gone wrong went wrong.

I got to a point where I couldn't fight it anymore. I was exhausted and I had to accept what was happening. There was a four month period where, for every day that I was functional, I had to spend two days in bed. You're in that mode and you're just thinking, “Well, I guess this is who I am now.” I went from this super high charged, ambitious person, and now I can barely get out of bed. I can barely function.

There was a moment of just accepting that that was what it was.

Time is a really beautiful, wonderful thing if you allow her to do the work and you stop getting in her way. I wish I could say the recovery was intentional, but I just didn't have a choice.

One day I woke up and I said: “Okay, enough of that. Time to get out of bed.”

I wish I had something more profound to say than just: I kind of gave up and let it happen and said, I'm done fighting this because I can't. I'm so tired.

Whenever I have these conversations and we talk about these crisis points, it always feels like it just happens, or one day it changes, but I think there's all this internal work that you're not seeing that's happening before that point.

I do aerial hoop as one of my hobbies. I think of that parallel a lot. When you start first start, there's just a lot of conditioning and it doesn't feel like you're getting to the point of that cool trick that you really want to do.

But you just keep conditioning. They keep coaching you on how to do this prep work and conditioning and you just keep doing it. It's all this invisible small tiny movement work.

Then one day, it does feel like the big, flashy trick just magically happens. You just are able to do it out of nowhere. I think that's probably true of our brains too.

I think also there's this element of just relinquishing control. The harder you grip, the more elusive the solution becomes. There's this moment where you just have to say, it is what it is. These are things beyond my control to change in this moment. I just need to relax and relinquish control and let what's going to happen happen.

Going back to water — this moment of dissolving into the water and becoming one with the water and letting the water do its work for a while.

Unfortunately we live in a society where productivity looks very specific to us. When you dissolve into water, that doesn't look productive, but in fact, that is allowing you to reconnect in a biological way to the rest of the world.

I love that we returned to water because I wanted to also ask about marine biology and why you think that was your childhood dream. How do you think your career circles back to the water?

I spent most of my childhood in South Bend, Indiana, until I was seven years old. When we moved to Massachusetts, I had never seen two things. The first was water — open water. The second was a hill!

I made some friends in Massachusetts and my parents took me on a whale watch and they said, “You can bring one friend.” You can imagine two little seven year olds on this boat. We hadn't seen anything that day. Finally, right at the end of this trip, we see all of these whales and the captain stays out too long and on the way back he has to really gun it to get back to the harbor on time. The boat is coming up and down and it's crashing into the waves. It's this really hard motion and we're moving really fast so we attract a pod of dolphins.

Because of the motion of the boat, everyone is totally seasick. So, they're inside the cabin and there are also lots of waves splashing over the sides of the boat. All these adults were like: “This is horrible.”

I saw an opportunity! Without thinking, I turned to my friend and said, “Come with me.”

I convinced her to go out to the bow of the boat, the front of the boat, and there's this little opening at the base of the deck and I said: “All right, grab my legs.”

I then shimmy out over the edge of this boat. She's holding onto my legs to make sure that I don't fall overboard. Can you even imagine this? I’m just this seven year old hanging way off the side of this boat. It's a miracle no one saw it and called child services. And as the boat comes down, a dolphin comes up, and my hand slides right across its back.

My friend, Christina, pulls me back onto the boat and I'm just completely losing it. I was ecstatic.

That was the moment I was hooked. Everything related to the ocean. When I tell people I wanted to be a marine biologist when I was seven, they say, “Oh, you wanted to be a dolphin trainer!” No, no, no, no, no. I wanted to study the neurotoxicology of dinoflagellates. I was a very nerdy kid. It was this world that I couldn't see that I wanted to understand better that had all of these fascinating creatures.

You see the surface and then you don't know what's underneath. It's this fascinating, beautiful world that opens up to you, if you are brave enough to enter it and discover it.

To tie it back to the work that I do now—we haven't even talked about growing up with a concert pianist for mom and music and what that does to your listening skills and this theme of listening through a career—but if we are just focused on this theme of water…

My whole career has come from honing the ability to see the the iceberg but know there's more, to step into uncertain, unknown situations and immediately see under the surface and understand: “Ah, these are the dynamics, these are the things that are causing pain. This is where the problem is.” Then, helping people to untangle that by inviting them to bring their head below water — so that they can see an entirely new world that was hidden to them.